To further improve our fundamental understanding of the effects of the topography and rotation on the climate, a team of scientists performed and analyzed simulations with the Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM), in which the rotation of Earth is reversed (retrograde). This reversal equals the creation of a mirror-image of the topography. The reversal conserves all major properties like the sizes of continents and ocean basins while creating vastly different conditions for the interactions between topography, weather systems and ocean currents.

As these interactions affect all parts of the climate system, a diverse team of twenty scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (MPI-M), the German Climate Computing Center (DKRZ), and the Universities of Hamburg and Reading combines their expertise in all parts of the climate system for the analysis of the simulations. The scientists are preparing a publication of their results and illustrate changes, ranging from the trivial to the unpredictable, in a series of graphics and animation videos.

Simulations

Earth’s rotation influences the climate in two ways. One is the direction of the apparent path of the Sun around the Earth, the other is the Coriolis effect, which deflects motions in a rotating system. The major challenge in performing this kind of simulations with a comprehensive general circulation model is the required degree of equilibration of the system. To reduce the model drift in the deep ocean to an acceptably small level, simulations of several thousand years are necessary. With the standard model set-ups, this would take several months to years of simulations on any supercomputer. To speed the simulations up, the coarse resolution setup of MPI-ESM is used in this study. The scientists conducted two experiments with pre-industrial climate conditions: one for prograde rotation (hereafter referred to as CNTRL) and one for retrograde rotation (RETRO).

Climate features of a retrograde rotating Earth

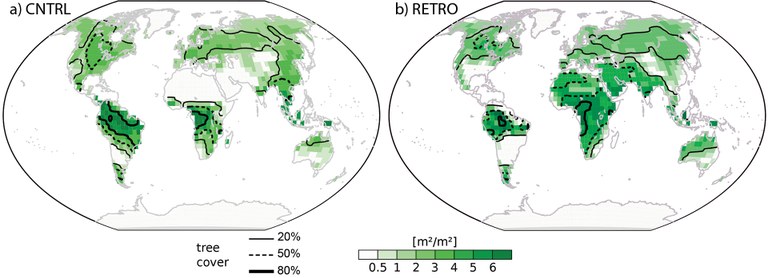

The global mean properties should in principle not be directly affected by a reversal of the direction of rotation, but feedbacks between different climatic processes can induce changes in the mean. In the simulations, the global means of the most important quantities change only marginally, and the global mean temperature in RETRO is just 0.18 K below the value in CNTRL. A notable exception is the globally integrated desert area. The retrograde world is greener as the desert area shrinks from about 42 Mio km2 to about 31 Mio km2. Half of the former desert area is covered by woody vegetation, the other half by grass. Consistently, the retrograde world stores more carbon in its terrestrial vegetation.

Even more drastic changes affect the climatic patterns. These changes can be grouped into changes directly following from the reversal of the Coriolis effect, like the reversal of atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns, and changes that result from interactions in the climate system. The most prominent of the latter are a reorganization of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a shift of the deep water formation from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific, drastic changes in the phytoplankton species composition in the Indian Ocean, and a relocation of the deserts.

Video 1: Surface temperature in CNTRL (left) and RETRO (right). In the tropics, the diurnal cycle of the sun reflects in surface temperature pulses moving from east to west in CNTRL, and from west to east in RETRO. In North America and Eurasia, the effects vary in the different seasons. In summer, the effect of the diurnal cycle is strong. In winter, the effect of the diurnal cycle is weak and the weather systems dominate the temperature variability. In CNTRL, the weather systems mainly travel from west to east. In RETRO, the winds reverse their direction and the weather systems travel westwards.

Direct consequences of the retrograde rotation

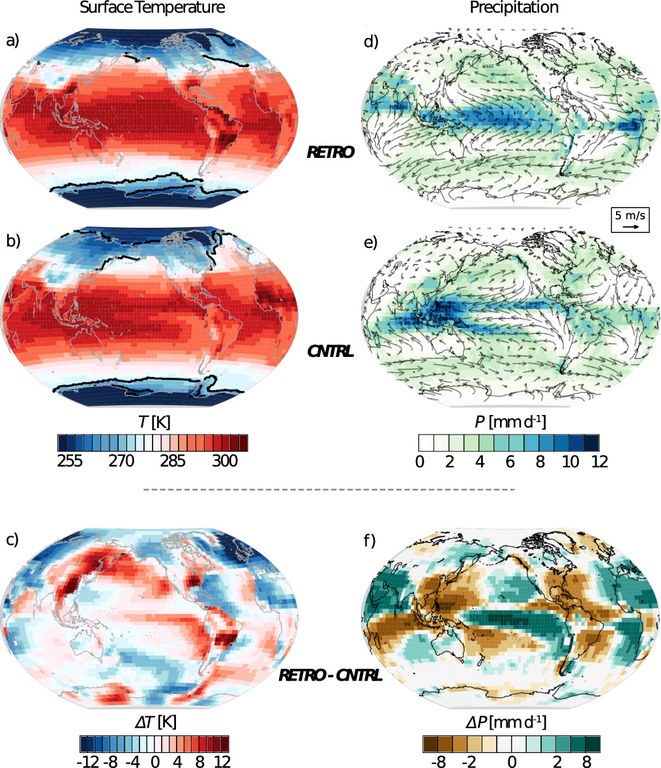

The expected consequence of a retrograde rotation is a reversal of the zonal wind patterns, resulting in easterly jets and westerly trade winds. Due to the reversed winds in RETRO, the continents in the subtropics and mid-latitudes become colder on their western and warmer on the eastern margins (Fig. 1), most prominent over Eurasia with a massive wintertime cooling over North West Europe.

Figure 1: Left column: Annual averaged surface temperature in RETRO (a), CNTRL (b), and difference between RETRO and CNTRL (c). Black isolines in (a) and (b) show summer and winter sea ice extent. Right column: Annual precipitation and 10m wind in RETRO (d), CNTRL (e), and difference between RETRO and CNTRL (f).

Similar to the winds, the ocean gyres reverse their directions and the western boundary currents like the Gulf Stream shift to the eastern sides of the ocean basins (Video 2). In the subtropics, this leads to a general warming on the eastern sides of the oceans and a cooling on the western sides. The Indian Ocean takes over the role of the tropical east Pacific with strong upwelling of cold subsurface water and a strong surface cooling.

Video 2: Ocean current velocities in CNTRL (left) and RETRO (right). The boundary currents switch from the western sides of the basins in CNTRL to the eastern sides in RETRO.

This upwelling provides a major source of nutrients like nitrate and phosphorus for phytoplankton (marine plants). Thus, changes in the ocean circulation propagate into patterns of biogeochemistry, such as the locations of high biological production. In contrast to the prograde world, in RETRO high production is found on the western sides of the ocean basins while the zonal mean production remains largely unchanged.

Effects of climatic interactions

Monsoon systems

Video 3: Precipitation for CNTRL (left) and RETRO (right). In the tropics, strong convective systems pulsate on a daily basis. The annual cycle shifts them to the north in summer, and to the south in winter. In RETRO, they reach into the Sahara Desert in summer and turn it into a forest. In the mid-latitudes, the cyclone systems follow the main flow of the atmosphere, moving eastward in CNTRL and westward in RETRO.

The reversed rotation of the Earth is accompanied by a strong reorganization of the ITCZ (Fig. 1, Video 3). While the strongest precipitation is centered in and around the warm-pool Asia-Australia monsoon complex in CNTRL, it shifts to a more tripolar structure with centers of action in the eastern tropical Atlantic, the central Pacific and a monsoon region centered in the Middle East in RETRO. This shift in the ITCZ is a response to changes in the stationary eddy transport and in the ocean circulation.

Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation

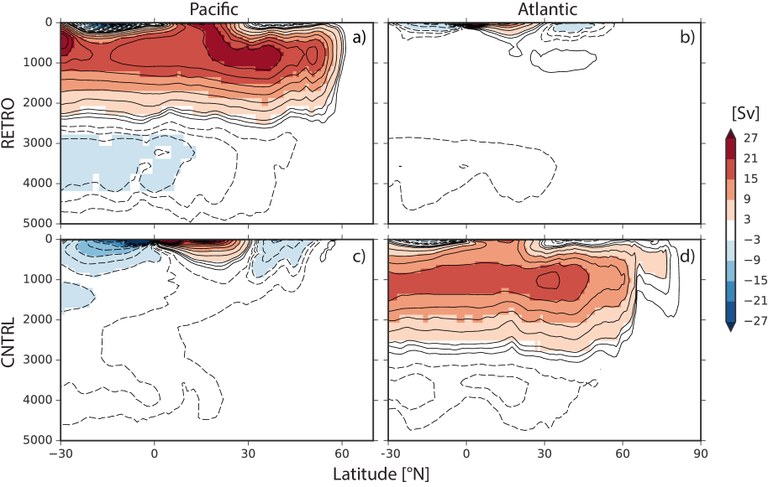

Another prominent difference between RETRO and CNTRL is the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (MOC) in the RETRO experiments (Fig. 2), with only sporadic formation of deep intermediate water in the North Atlantic, contradicting a previous study [1]. Instead, a strong overturning cell emerges in the Pacific. The Pacific MOC in RETRO is similar in structure but slightly stronger than the Atlantic MOC in CNTRL.

Figure 2: MOC stream functions in the Pacific Ocean (left) and the Atlantic (right) for RETRO (top) and CNTRL (bottom). Positive values indicate clockwise rotation with northward flow in the upper and southward flow in the lower part of a circulation cell. 1 Sv corresponds to a transport of 106 m3/s. The Pacific in RETRO takes over the role of the Atlantic in CNTRL.

The breakdown of the Atlantic MOC and the associated decrease in meridional heat transport lead to a cooling of the North Atlantic associated with a southward extension of sea ice and a significant cooling over Europe (Fig. 1, Video 1). The accompanying southward shift of the temperature maximum over the tropical Atlantic contributes to the southward shift of the Atlantic ITCZ (Fig. 2). In contrast, the Pacific MOC in RETRO, characterized by an enhanced northward transport of heat along the West coast of North America, results in a significant warming of the North Pacific (Fig. 1 for the warming, Video 2 for the currents). The reversed atmospheric circulation leads to advection of this heat anomaly into the eastern parts of Russia.

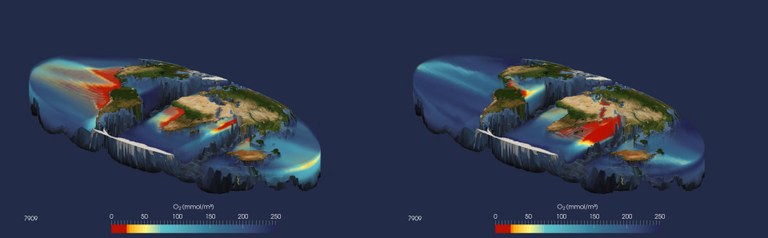

Phytoplankton

The changes in the ocean circulation in the Indian Ocean in RETRO have an unexpected consequence on the marine species composition. They create conditions that favor cyanobacteria over other phytoplankton species on a large scale. This is not observed anywhere on the prograde world. Globally, the dominant biological producer is phytoplankton that can meet its nitrogen needs solely from dissolved nitrate. Only some specialized phytoplankton species, cyanobacteria, are independent of nitrate supply as they are able to fix elemental nitrogen. In the prograde world cyanobacteria are outcompeted by nitrate consuming phytoplankton species almost everywhere and contribute only a few percent to marine organic matter production. In contrast, in RETRO, cyanobacteria become the dominant biological producers in northern Indian Ocean. Strong equatorial upwelling in the Indian Ocean leads to an increase in biological production with subsequent oxygen consumption due to remineralization of this organic matter at depth. The special basin geometry of the Indian Ocean with a northern landmass and the resulting ocean circulation lead to poor ventilation and the formation of an extended oxygen minimum zone (OMZ, Fig. 3). OMZs are the only habitat for denitrifying microorganisms which use nitrate instead of oxygen to degrade organic matter and thereby produce phosphate. Upwelling of this phosphate enriched and nitrate depleted water in the northern Indian Ocean creates favorable growth conditions for cyanobacteria. Thus, the reversed Earth rotation shapes a phytoplankton species composition with a dominance of cyanobacteria in a large ocean region which has never been observed in the prograde world.

Figure 3: Ocean oxygen content in CNTRL (left) and RETRO (right). Low oxygen content is a consequence of high biological production and the decomposition of sinking organic matter. Notice the massive oxygen minimum zone developing in the Indian Ocean in RETRO.

Deserts

Figure 4: Leaf area index and tree cover for a) CNTRL and b) RETRO. The leaf area index is the ratio between the one-sided leaf surface area in a grid cell and the ground surface area. Notice the greening of the vast desert band in the Sahara and Arabia in RETRO.

Also on the land, life is affected by the reversal of the rotation. The changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulations are accompanied by a warming and strong drying in the lee of the Andes over South America, the North China Plain in East Asia and the east-southeast coast of the US. Southern Brazil and Argentina become the Earth’s biggest deserts and the Southern States of the US see a dramatic climate shift from a fully humid climate towards a complete aridification. In contrast, the climate in North Africa and in Southwest Asia becomes cooler and wetter in RETRO and the Sahara and the Arabian Desert greens (Fig. 4). One of the most non-trivial changes is the complete replacement of the wide desert belt from West Africa to the Middle East in CNTRL by more moderate, humid climates in RETRO. In general, many dry regions are simulated in RETRO, but extreme deserts - like the present-day Sahara - are much less wide spread.

Consumption of resources at the DKRZ

The simulations of the project needed about 1.2 million processor hours on the supercomputer of the DKRZ. It took abaout one node hour to calulate one simulation year. In total, about 80 terabytes of climate data were calculated and archived. The results are currently being reviewed for publication in Earth System Dynamics [2].

The model results were visualized as pictures and videos with the support of the DKRZ visualization groups. These visualizations are presented on the DKRZ's new interactive climate touch table. This was used already shown at the 4th ICESM in Hamburg, at the Science Night as well as at the conferences SC`17 and ISC`18.

Figure 5: Visitors at the Science Night (November 4, 2017) gather information on the impact of a retrograde earth on the climate at the interactive touch table (Source: © UHH-CEN, Porsack)

Contact

- Dr. Florian Ziemen, Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (Zmxvcmlhbi56aWVtZW5AbXBpbWV0Lm1wZy5kZQ==)

- Uwe Mikolajewicz, Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (dXdlLm1pa29sYWpld2ljekBtcGltZXQubXBnLmRl)

- Dr. Marie-Luise Kapsch, Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (bWFyaWUtbHVpc2Uua2Fwc2NoQG1waW1ldC5tcGcuZGU=)

Publications:

[1] V. Kamphuis, S. E. Huisman, and H. A. Dijkstra: The global ocean circulation on a retrograde rotating earth, Climate of the Past, 2011, doi: 10.5194/cp-7-487-2011.

[2] Mikolajewicz, U., Ziemen, F., Cioni, G., Claussen, M., Fraedrich, K., Heidkamp, M., Hohenegger, C., Jimenez de la Cuesta, D., Kapsch, M.-L., Lemburg, A., Mauritsen, T., Meraner, K., Röber, N., Schmidt, H., Six, K. D., Stemmler, I., Tamarin-Brodsky, T., Winkler, A., Zhu, X., and Stevens, B.: The climate of a retrograde rotating earth, Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-2018-31, in review, 2018. https://www.earth-syst-dynam-discuss.net/esd-2018-31/